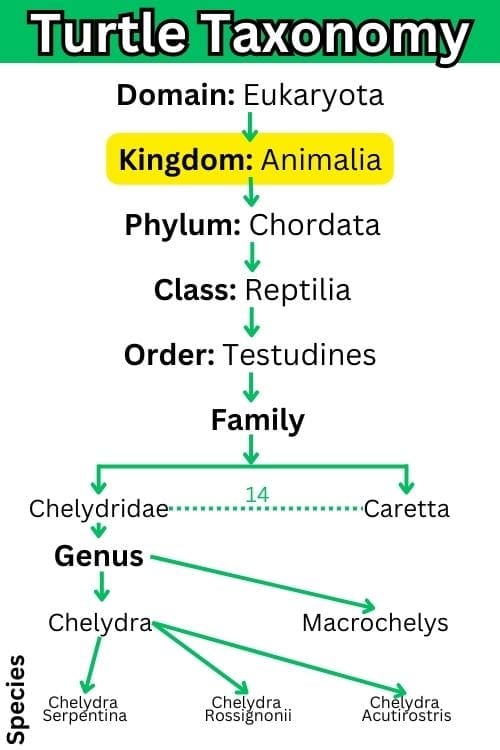

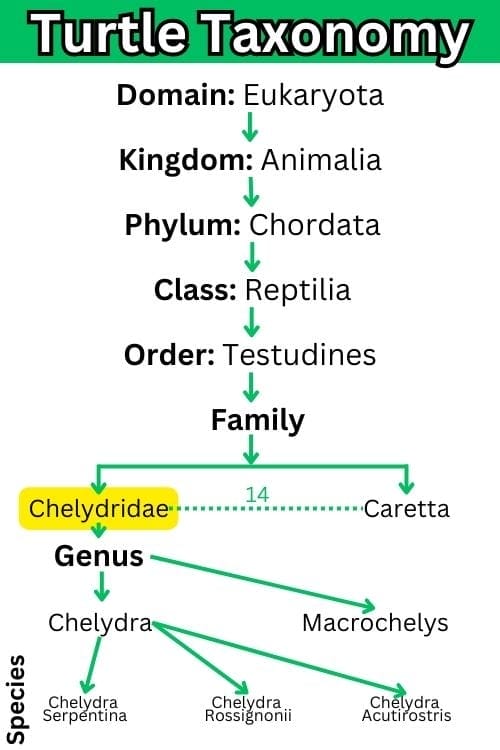

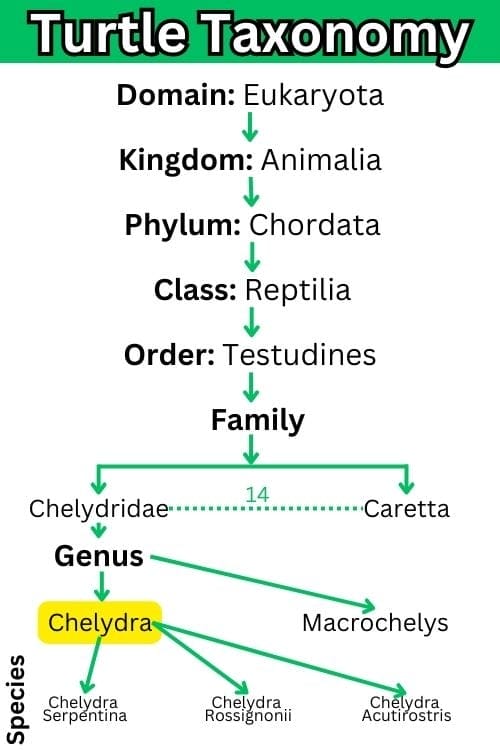

Turtle Taxonomy: Complete Classification Guide [Domain to Species]

This post was created with help from AI tools and carefully reviewed by a human (Muntaseer Rahman). For more on how we use AI on this site, check out our Editorial Policy.

Turtle taxonomy is the scientific classification system that organizes all 350+ turtle and tortoise species into hierarchical categories.

Every turtle belongs to Order Testudines under Class Reptilia, but species are further divided into 14 families, numerous genera, and individual species based on evolutionary relationships and physical characteristics.

This guide explains each classification level from domain to species, using snapping turtles as a detailed example.

Turtle Taxonomy Quick Reference

| Classification Level | All Turtles Share | Examples of Division |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukaryota | (All complex life) |

| Kingdom | Animalia | (All animals) |

| Phylum | Chordata | (All vertebrates) |

| Class | Reptilia | (Snakes, lizards, crocodiles, turtles) |

| Order | Testudines | (All 350+ turtle/tortoise species) |

| Family | 14 families | Sea turtles, tortoises, snapping turtles, etc. |

| Genus | 95+ genera | Chelydra, Macrochelys, Trachemys, etc. |

| Species | 350+ species | Common snapping turtle, red-eared slider, etc. |

Example Full Classification:

Common Snapping Turtle = Chelydra serpentina

- Domain: Eukaryota → Kingdom: Animalia → Phylum: Chordata → Class: Reptilia → Order: Testudines → Family: Chelydridae → Genus: Chelydra → Species: serpentina

Understanding Biological Classification Levels

Biological taxonomy uses a hierarchical system where each level becomes more specific. Think of it like organizing addresses: Country → State → City → Street → House Number. With animals, we go from Domain (broadest) down to Species (most specific).

The first five levels are the same for all turtles and tortoises. After Order Testudines, turtles split into different families, genera, and species based on their unique characteristics and evolutionary history.

This Hilarious Turtle Book Might Know Your Pet Better Than You Do

Let’s be real—most turtle care guides feel like reading a textbook written by a sleep-deprived zookeeper.

This one’s not that.

Told from the snarky point of view of a grumpy, judgmental turtle, 21 Turtle Truths You’ll Never Read in a Care Guide is packed with sarcasm, sass, and surprisingly useful insights.

And hey—you don’t have to commit to the whole thing just yet.

Grab 2 free truths from the ebook and get a taste of what your turtle really thinks about your setup, your food choices, and that weird plastic palm tree.

It’s funny, it’s honest, and if you’ve ever owned a turtle who glares at you like you’re the problem—you’ll feel seen.

Domain: Eukaryota (All Complex Life)

Domain is the highest classification level in biology. All life on Earth falls into one of three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, or Eukarya.

Turtles belong to Domain Eukarya, which includes all organisms whose cells have a nucleus containing genetic material. This domain encompasses animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Essentially everything you can see without a microscope belongs to Eukarya.

What makes Eukarya different:

Unlike bacteria and archaea (which are single-celled organisms without a nucleus), eukaryotic cells are complex with specialized internal structures called organelles. This cellular complexity allows for the development of multicellular organisms like turtles.

Kingdom: Animalia (All Animals)

Kingdom is the second classification level, sitting directly below domain. Within Domain Eukarya, there are four main kingdoms: Animalia (animals), Plantae (plants), Fungi (mushrooms, molds), and Protista (mostly single-celled organisms).

Turtles belong to Kingdom Animalia. All animals share several key characteristics:

Multicellular structure: Animal bodies are made of many specialized cells organized into tissues and organs.

Heterotrophic feeding: Animals cannot make their own food like plants. They must eat other organisms for energy.

Mobility: Most animals can move independently, especially during early life stages. Turtles demonstrate this through swimming, walking, or both depending on species.

Complex cell organization: Animal cells have sophisticated structures but lack the rigid cell walls found in plants.

Phylum: Chordata (All Vertebrates)

Phylum groups organisms that share major structural characteristics. Within Kingdom Animalia, there are approximately 35 phyla, including Arthropoda (insects, spiders, crustaceans), Mollusca (snails, clams, octopuses), and Chordata (animals with backbones).

Turtles belong to Phylum Chordata. The defining feature of chordates is having a notochord (a flexible rod-like structure) at some point in their development.

In most chordates, including turtles, this notochord develops into a backbone (vertebral column).

Key chordate characteristics:

- Dorsal nerve cord: A nerve cord running along the back that develops into the spinal cord.

- Pharyngeal slits: Openings in the throat area (present during embryonic development).

- Post-anal tail: A tail extending beyond the digestive tract.

- Backbone: In vertebrates like turtles, the notochord becomes a bony or cartilaginous spine.

The majority of Phylum Chordata consists of vertebrates (animals with backbones), which include fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Class: Reptilia (All Reptiles)

Class sits below phylum and groups animals with similar anatomical and physiological features. Within Phylum Chordata, there are seven main classes including fish (multiple classes), amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Turtles belong to Class Reptilia. Reptiles are characterized by specific traits that distinguish them from other vertebrates:

Cold-blooded metabolism: Reptiles rely on external heat sources to regulate body temperature. Turtles bask in sunlight to warm up and seek shade or water to cool down.

Scaly skin: Reptile skin is covered in scales made of keratin (the same protein in human fingernails). This waterproof covering prevents water loss and allows reptiles to live in dry environments.

Amniotic eggs: Reptiles lay eggs with protective shells and internal membranes that prevent dehydration. This adaptation freed reptiles from needing to lay eggs in water like amphibians.

Direct development: Baby reptiles hatch looking like miniature adults. There is no larval stage or metamorphosis like in amphibians.

Other members of Class Reptilia:

Snakes and lizards (Order Squamata) are the most diverse reptile group with over 10,000 species. They have overlapping scales and flexible bodies.

Crocodiles and alligators (Order Crocodylia) are large semi-aquatic predators with powerful jaws and armored skin.

Tuataras (Order Rhynchocephalia) are rare lizard-like reptiles found only in New Zealand. They are the sole survivors of an ancient reptile lineage.

Order: Testudines (All Turtles and Tortoises)

Order is the classification level below class. Within Class Reptilia, there are four orders, and turtles have their own distinct order.

Turtles and tortoises belong to Order Testudines, also called Order Chelonia. This order includes approximately 350 living species found on every continent except Antarctica.

Defining characteristics of Order Testudines:

Shell structure: All turtles have a protective shell made of bone covered by either scutes (hard plates) or leathery skin. The shell consists of two parts: the carapace (top) and plastron (bottom).

Fused skeleton: Unlike other reptiles, a turtle’s shell is fused to its ribcage and spine. Turtles cannot leave their shells because the shell is part of their skeleton.

Beak instead of teeth: Turtles lost their teeth millions of years ago. They have hard, keratinized beaks for biting food.

Retractable limbs: Most turtles can pull their head and legs into their shell for protection, though some species have limited retraction ability.

Long lifespan: Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Many species live 50-100 years, and some giant tortoises exceed 150 years.

The name “Testudines” comes from the Latin word testudo, meaning “tortoise” or “shell-covered.” This order has existed for over 220 million years, making turtles one of the oldest living reptile groups.

The 14 Turtle Families Under Order Testudines

Order Testudines is divided into 14 families based on shell structure, habitat, evolutionary history, and anatomical features. Each family represents a distinct evolutionary lineage with specialized adaptations.

Family Cheloniidae (Hard-Shelled Sea Turtles)

Common Name: Sea Turtles

Characteristics: Large marine turtles with streamlined shells and paddle-shaped flippers. Cannot retract head or limbs into shell. Adapted for oceanic life with salt glands to expel excess salt.

Habitat: Open ocean and coastal waters worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions.

Examples: Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta).

Number of Species: 6 species

Family Dermochelyidae (Leatherback Sea Turtles)

Common Name: Leatherback Turtles

Characteristics: The largest living turtles, reaching over 6 feet in length and weighing up to 2,000 pounds. Unlike all other turtles, they have a flexible, leathery shell instead of hard scutes. Seven ridges run lengthwise along the carapace.

Habitat: Open ocean waters worldwide, from tropical to subarctic regions. Dive deeper than any other turtle (over 4,000 feet).

Examples: Leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

Number of Species: 1 species (the only surviving member of this ancient family)

Family Testudinidae (Tortoises)

Common Name: Tortoises

Characteristics: Land-dwelling turtles with high-domed shells and elephantine legs adapted for walking. Cannot swim. Exclusively herbivorous. Known for extreme longevity (often 80-150+ years).

Habitat: Land environments ranging from deserts to grasslands to forests. Found on all continents except Australia and Antarctica.

Examples: Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis niger), African spurred tortoise (Centrochelys sulcata), Russian tortoise (Testudo horsfieldii).

Number of Species: Approximately 50 species

Important note: All tortoises are turtles (they belong to Order Testudines), but not all turtles are tortoises. Tortoises are specifically the terrestrial members of one family within the larger turtle order.

Family Emydidae (Pond and Box Turtles)

Common Name: Pond Turtles and Box Turtles

Characteristics: Medium-sized freshwater and semi-aquatic turtles with hard, bony shells. Many species have hinged plastrons allowing them to close their shells completely. Often have colorful markings.

Habitat: Ponds, lakes, streams, and marshes primarily in North America. Some species (box turtles) are terrestrial.

Examples: Red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), painted turtle (Chrysemys picta), Eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina).

Number of Species: Approximately 50 species

This is the most common family kept as pets. Red-eared sliders are among the most popular pet turtles worldwide.

Family Geoemydidae (Asian River Turtles)

Common Name: Asian River Turtles, Leaf Turtles, Roofed Turtles

Characteristics: Diverse family with species ranging from aquatic to semi-terrestrial. Many have intricate shell patterns and colorful markings on head and neck. Shell shapes vary widely across species.

Habitat: Rivers, streams, and forests throughout Asia. Some species are highly aquatic, others terrestrial.

Examples: Red-crowned roof turtle (Batagur kachuga), black marsh turtle (Siebenrockiella crassicollis), Chinese box turtle (Cuora flavomarginata).

Number of Species: Approximately 70 species

Family Trionychidae (Softshell Turtles)

Common Name: Softshell Turtles

Characteristics: Flat, pancake-like turtles with leathery shells lacking hard scutes. Long, tubular snouts act as snorkels. Webbed feet make them excellent swimmers. Can breathe underwater through their skin and throat lining.

Habitat: Rivers, lakes, and ponds with soft, muddy bottoms. Found in North America, Africa, and Asia.

Examples: Smooth softshell turtle (Apalone mutica), spiny softshell turtle (Apalone spinifera), Chinese softshell turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis).

Number of Species: Approximately 30 species

Family Kinosternidae (Mud and Musk Turtles)

Common Name: Mud Turtles and Musk Turtles

Characteristics: Small turtles (4-6 inches typically) with hinged plastrons that close partially. Musk turtles release a strong odor when threatened. Generally dark-colored shells.

Habitat: Slow-moving waters, ponds, and muddy swamps in North and South America.

Examples: Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum), common musk turtle or “stinkpot” (Sternotherus odoratus), razor-backed musk turtle (Sternotherus carinatus).

Number of Species: Approximately 25 species

Family Chelydridae (Snapping Turtles)

Common Name: Snapping Turtles

Characteristics: Large freshwater turtles with powerful jaws and aggressive defensive behavior. Reduced plastrons (bottom shells) leave legs exposed. Long, muscular tails. Poor swimmers despite aquatic lifestyle.

Habitat: Freshwater lakes, rivers, and swamps in North and Central America and northern South America.

Examples: Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina), alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii).

Number of Species: 6 species across 2 genera

We will examine this family in detail later as our case study.

Family Pelomedusidae (African Side-Necked Turtles)

Common Name: African Side-Necked Turtles or Hidden-Necked Turtles

Characteristics: Cannot retract neck straight back into shell. Instead, they fold their neck sideways to tuck head under the front edge of the carapace. Most species have relatively flat shells.

Habitat: Freshwater lakes, rivers, and temporary ponds in Africa and Madagascar.

Examples: African helmeted turtle (Pelomedusa subrufa), African mud turtle (Pelusios castaneus).

Number of Species: Approximately 18 species

Family Podocnemididae (South American Side-Necked River Turtles)

Common Name: South American Side-Necked Turtles or Podocnemis River Turtles

Characteristics: Like African side-necks, these turtles fold their necks sideways. Generally larger than their African relatives. Some species are highly aquatic while others are more adaptable.

Habitat: Major river systems in South America, particularly the Amazon and Orinoco basins. Also found in Madagascar.

Examples: South American river turtle (Podocnemis expansa), yellow-spotted Amazon river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis).

Number of Species: Approximately 8 species

Family Carettochelyidae (Pig-Nosed Turtles)

Common Name: Pig-Nosed Turtles or Fly River Turtles

Characteristics: Unique turtles with fleshy, pig-like snouts. Leathery shells similar to softshell turtles but more rigid. Front limbs modified into flippers like sea turtles despite being freshwater species.

Habitat: Rivers, lagoons, and estuaries in northern Australia and southern New Guinea.

Examples: Pig-nosed turtle (Carettochelys insculpta)

Number of Species: 1 species (sole surviving member of its family)

Family Chelidae (Australasian Side-Necked Turtles)

Common Name: Snake-Necked Turtles or Austro-American Side-Necked Turtles

Characteristics: Side-necked turtles with extremely long necks in some species. Wide, flattened shells. Entirely aquatic or semi-aquatic. Some species have necks nearly as long as their shells.

Habitat: Freshwater habitats in Australia, New Guinea, and parts of South America.

Examples: Eastern long-necked turtle (Chelodina longicollis), mata mata (Chelus fimbriata), twist-necked turtle (Platemys platycephala).

Number of Species: Approximately 60 species

Family Platysternidae (Big-Headed Turtles)

Common Name: Big-Headed Turtles

Characteristics: Small turtles with disproportionately large heads that cannot retract into their shells. Flattened shells with serrated rear edges. Excellent climbers that scale rocks and fallen trees using their powerful limbs and long tails.

Habitat: Fast-flowing mountain streams in Southeast Asia (Myanmar, Thailand, China, Vietnam, Laos).

Examples: Big-headed turtle (Platysternon megacephalum)

Number of Species: 1 species (though some taxonomists recognize multiple subspecies)

Family Dermatemydidae (Central American River Turtles)

Common Name: Central American River Turtles or Mesoamerican River Turtles

Characteristics: Large aquatic turtles with smooth, oval shells. Strictly herbivorous as adults. Webbed feet but poor swimmers compared to other aquatic turtles. Critically endangered.

Habitat: Large rivers and lakes in southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize.

Examples: Central American river turtle (Dermatemys mawii)

Number of Species: 1 species (only surviving member of this ancient family)

Family Chelydridae: A Detailed Case Study

To demonstrate how taxonomy works beyond the family level, we will examine Family Chelydridae (snapping turtles) in detail.

This family provides an excellent example of how species are organized into genera based on shared characteristics and evolutionary relationships.

Family Chelydridae consists of two distinct genera, each containing three species. While all six species share the fundamental traits of snapping turtles (powerful jaws, aggressive defense, reduced plastrons, ambush predation), they differ enough to warrant separation into two evolutionary lineages.

The Two Genera of Snapping Turtles

Genus Chelydra (Common Snapping Turtles)

Genus Chelydra includes the common snapping turtles found throughout the Americas. These are medium to large turtles (8-18 inches shell length, 10-35 pounds) with rough, keeled shells and long, saw-toothed tails.

Distinctive characteristics:

- Rough, ridged carapace with three prominent keels running lengthwise.

- Long tail with triangular scales resembling a dinosaur’s tail.

- More active hunters that pursue prey rather than using lure-and-wait tactics.

- Can walk relatively well on land compared to alligator snapping turtles.

- Found in various aquatic habitats from small ponds to large lakes.

Defensive behavior: When out of water, common snapping turtles are aggressive and will strike with surprising speed. In water, they typically flee rather than fight.

Genus Macrochelys (Alligator Snapping Turtles)

Genus Macrochelys contains the alligator snapping turtles, which are among the largest freshwater turtles in the world. These prehistoric-looking reptiles can exceed 200 pounds and reach shell lengths over 2 feet.

Distinctive characteristics:

- Heavily spiked shell with three pronounced ridges creating an armored appearance.

- Massive triangular heads with hooked beaks capable of tremendous bite force.

- Unique hunting method: pink, worm-like tongue appendage lures fish into striking range.

- Sedentary lifestyle; spend most of their time motionless on river bottoms.

- Found only in specific river systems draining into the Gulf of Mexico.

Hunting strategy: Alligator snapping turtles use aggressive mimicry. They lie motionless on the riverbed with their mouths open, wiggling the worm-like appendage on their tongue. When fish investigate, the turtle snaps its jaws shut with devastating force.

The distinction between these two genera reflects millions of years of evolutionary divergence. While they share a common ancestor and the fundamental snapping turtle body plan, each genus adapted to different ecological niches with specialized hunting strategies.

The Three Species of Genus Chelydra

Chelydra serpentina (Common Snapping Turtle)

Geographic Range: Southeastern Canada through the United States to the Gulf of Mexico and into northeastern Mexico. The most widespread snapping turtle species.

Habitat: Highly adaptable. Found in ponds, lakes, rivers, marshes, swamps, and even brackish estuaries. Prefers slow-moving or still waters with soft, muddy bottoms and abundant vegetation.

Physical Description:

- Shell length: 8-18 inches (occasionally larger)

- Weight: 10-35 pounds (rarely exceeding 40 pounds)

- Carapace color: Tan, brown, or black, often covered with algae

- Three prominent keels on carapace

- Plastron: Small and cross-shaped, yellowish color

- Tail: Nearly as long as the carapace

Behavior: Active predators that hunt fish, frogs, small birds, carrion, and aquatic plants. Notorious for their aggressive behavior when encountered on land. Can live 30-50 years in the wild.

Conservation Status: Least Concern (stable populations despite harvesting for soup trade)

Chelydra rossignonii (Central American Snapping Turtle)

Geographic Range: Southern Mexico through Central America into northwestern Colombia. Separated from C. serpentina by geographic range and genetic differences.

Habitat: Rivers, lakes, and swamps in tropical lowland regions. Prefers larger bodies of water than C. serpentina.

Physical Description: Very similar in appearance to C. serpentina but generally inhabits warmer climates. Distinguishing features include subtle differences in shell shape and scalation patterns.

- Shell length: 10-18 inches

- Weight: 15-35 pounds

- Slightly more pronounced keels than C. serpentina

Behavior: Similar predatory lifestyle to common snapping turtle. Less studied due to more restricted range and habitat preference for remote waterways.

Conservation Status: Data Deficient (population status unclear, likely threatened by habitat loss)

This species was only recognized as distinct from C. serpentina relatively recently based on genetic analysis and geographic isolation.

Chelydra acutirostris (South American Snapping Turtle)

Geographic Range: Northwestern South America, primarily in Colombia, Ecuador, and possibly Venezuela. The southernmost snapping turtle species.

Habitat: Tropical rivers and wetlands in the Amazon basin foothills and Pacific coastal drainages.

Physical Description:

- Shell length: 10-16 inches

- Weight: 12-30 pounds

- Slightly more elongated snout than other Chelydra species (reflected in scientific name acutirostris meaning “sharp-snouted”)

- Carapace often darker than North American relatives

Behavior: Adapted to warmer, more tropical conditions than its northern cousins. Likely fills similar ecological role as other common snapping turtles but in South American ecosystems.

Conservation Status: Data Deficient (very little research on wild populations)

This species was only recently split from C. rossignonii based on genetic studies revealing sufficient differences to warrant species status.

The Three Species of Genus Macrochelys

Macrochelys temminckii (Alligator Snapping Turtle)

Geographic Range: River systems draining into the Gulf of Mexico from the Suwannee River in Florida west to East Texas. Historically found as far north as southeastern Kansas and Illinois.

Habitat: Deep, slow-moving rivers and large oxbow lakes. Rarely leaves water except during nesting season. Prefers areas with submerged logs and deep pools.

Physical Description:

- Shell length: 16-32 inches (occasionally larger)

- Weight: 70-200 pounds (record exceeds 200 pounds)

- Dark brown to gray carapace covered with algae and moss

- Three extremely prominent spiked ridges

- Massive head constituting significant percentage of body weight

Hunting Strategy: Lies motionless on river bottom for hours or days, mouth agape, wiggling pink tongue appendage. When fish approaches, jaws snap shut with estimated bite force exceeding 1,000 pounds per square inch.

Behavior: Almost entirely aquatic. Extremely sedentary with very small home ranges. Can remain underwater for 40-50 minutes between breaths. Lives 80-120 years potentially.

Conservation Status: Vulnerable (declining due to overharvesting for meat and habitat degradation)

This is the largest species and the one most people reference when discussing alligator snapping turtles. It was the only recognized species in the genus until genetic research revealed the other two.

Macrochelys suwanniensis (Suwannee Alligator Snapping Turtle)

Geographic Range: Restricted to the Suwannee River watershed in northern Florida and southern Georgia. The most geographically limited snapping turtle species.

Habitat: Similar to M. temminckii but specifically adapted to the unique blackwater river ecosystem of the Suwannee River system.

Physical Description:

- Shell length: 15-28 inches

- Weight: 60-150 pounds (generally smaller than M. temminckii)

- Shell morphology similar to M. temminckii but with subtle differences in spike formation and shell shape

- Genetic analysis shows distinct lineage separated from other Macrochelys for over 5 million years

Behavior: Nearly identical hunting and lifestyle to M. temminckii. The primary differences are genetic and geographic rather than behavioral.

Conservation Status: Vulnerable (extremely limited range makes population susceptible to localized threats)

This species was only officially recognized in 2014 when genetic studies revealed significant differentiation from M. temminckii. The Suwannee River’s isolation created a separate evolutionary path.

Macrochelys apalachicolae (Apalachicola Alligator Snapping Turtle)

Geographic Range: Apalachicola River system in the Florida Panhandle, including the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers in Georgia and Alabama.

Habitat: Large rivers with moderate to swift current. Found in deeper sections with rocky or sandy bottoms rather than the muddy substrates preferred by other species.

Physical Description:

- Shell length: 16-29 inches

- Weight: 65-175 pounds

- Morphologically intermediate between M. temminckii and M. suwanniensis

- Shell spikes slightly less pronounced than other species

- Darker overall coloration adapted to tannin-stained waters

Behavior: Hunting strategy identical to other alligator snapping turtles. May be slightly more active hunter based on habitat characteristics but research is limited.

Conservation Status: Vulnerable (limited range and ongoing habitat threats)

Like M. suwanniensis, this species was only recognized as distinct in recent years. The Apalachicola River system’s geographic isolation allowed for genetic divergence from the other populations.

The recognition of three separate Macrochelys species highlights how modern genetic analysis has revolutionized our understanding of turtle taxonomy. What scientists long believed was a single widespread species turned out to be three distinct lineages isolated in separate river systems.

Key Taxonomy Concepts to Remember

All tortoises are turtles.

Family Testudinidae (tortoises) falls under Order Testudines (turtles). Saying “not a turtle, it’s a tortoise” is technically incorrect. The proper distinction is “terrestrial turtle” versus “aquatic turtle.”

Not all turtles are tortoises.

There are 13 other families besides Testudinidae. Sea turtles, snapping turtles, softshells, and pond turtles are all turtles but not tortoises.

Genus and species names are italicized.

When writing scientifically, always italicize: Chelydra serpentina, Trachemys scripta, Testudo graeca. The genus is capitalized, the species is lowercase.

Species names are binomial.

Every species has a two-part scientific name: Genus + species. Chelydra is the genus, serpentina is the specific epithet. Together they form the species name.

Common names vary by region.

A red-eared slider might be called different names in different countries, but Trachemys scripta elegans is universal worldwide.

Taxonomy is always evolving.

New genetic research frequently reclassifies species or recognizes new species. The three Macrochelys species were only officially split in the 2010s despite existing for millions of years.

Subspecies add a third name.

When species have distinct regional varieties that can still interbreed, they are designated as subspecies with a trinomial name. For example, the red-eared slider is Trachemys scripta elegans (three parts).

Understanding Turtle Taxonomy in Practice

Turtle taxonomy provides the framework for scientific communication, conservation efforts, and hobbyist knowledge. When a researcher publishes findings about Chelydra serpentina, there is no confusion about which turtle they studied.

Common names can be ambiguous, but scientific names are precise.

Taxonomic classification also reveals evolutionary relationships. All members of Family Chelydridae share common ancestors and similar traits such as powerful jaws, aggressive defense behaviors, aquatic ambush hunting strategies, and reduced plastrons.

Yet within that family, the two genera represent distinct evolutionary pathways adapted to different hunting methods and habitats.

The hierarchical system allows scientists to discuss turtles at various levels of specificity.

A conservation biologist might discuss threats to Order Testudines as a whole (habitat loss, climate change, poaching), threats specific to Family Cheloniidae (fishing nets, plastic pollution, beach development), or threats to a particular species like Caretta caretta (loggerhead sea turtle population decline in Mediterranean).

For turtle keepers and hobbyists, understanding taxonomy helps identify species correctly, research appropriate care requirements, and avoid confusion between similar-looking turtles.

A pet store selling “sliders” might carry red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans), yellow-bellied sliders (Trachemys scripta scripta), or Cumberland sliders (Trachemys scripta troostii). While closely related subspecies, they have different natural ranges and subtle care differences.

Modern genetic analysis continues to refine turtle taxonomy. Species once thought to be single widespread populations are being split into multiple distinct species as DNA sequencing reveals hidden diversity.

The three Macrochelys species serve as prime examples. Conversely, some populations once considered separate species have been combined when genetic evidence shows insufficient differentiation.

As climate change, habitat loss, and other human impacts threaten turtle populations worldwide, accurate taxonomy becomes crucial for conservation. We cannot protect what we cannot identify and classify.

Understanding that the Suwannee alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys suwanniensis) is a distinct species restricted to one river system helps conservationists prioritize protection efforts for that vulnerable population.

Taxonomy is not merely academic classification. It is the fundamental language of biology that allows humans to understand, study, and protect the incredible diversity of turtle species that have survived on Earth for over 220 million years.

Turtle Taxonomy FAQs

What is turtle taxonomy?

Turtle taxonomy is the scientific classification system that organizes all turtle and tortoise species into hierarchical categories based on evolutionary relationships and physical characteristics. It ranges from broad categories (Domain, Kingdom, Phylum) to specific ones (Family, Genus, Species).

What order do turtles belong to?

All turtles and tortoises belong to Order Testudines (also called Order Chelonia). This order contains approximately 350 living species divided into 14 families. Order Testudines is the only surviving order of its kind, with all other prehistoric turtle orders extinct.

How many turtle families are there?

There are 14 recognized turtle families under Order Testudines:

- Cheloniidae (sea turtles)

- Dermochelyidae (leatherbacks)

- Testudinidae (tortoises)

- Emydidae (pond turtles)

- Geoemydidae (Asian river turtles)

- Trionychidae (softshells)

- Kinosternidae (mud and musk turtles)

- Chelydridae (snapping turtles)

- Pelomedusidae (African side-necks)

- Podocnemididae (South American side-necks)

- Carettochelyidae (pig-nose turtles)

- Chelidae (Australasian side-necks)

- Platysternidae (big-headed turtles) and

- Dermatemydidae (Central American river turtles)

What is the difference between genus and species in turtle classification?

Genus is a broader category that groups closely related species sharing a recent common ancestor and similar characteristics.

Species is the most specific classification representing individual populations that can interbreed and produce fertile offspring.

For example, genus Chelydra contains three species of common snapping turtles that evolved from a shared ancestor but are now genetically and geographically distinct.

Are all tortoises turtles?

Yes, all tortoises are turtles. Tortoises belong to Family Testudinidae, which is one of 14 families under Order Testudines (turtles). The term “tortoise” refers specifically to terrestrial turtles with adaptations for life on land.

However, not all turtles are tortoises. The other 13 families include sea turtles, snapping turtles, pond turtles, softshell turtles, and more.

What does Testudines mean?

Testudines is the scientific name for the taxonomic order that includes all living turtles and tortoises. The name derives from the Latin word testudo, meaning “tortoise” or “shell-covered creature.”

This order is also sometimes called Chelonia, from the Greek word chelone meaning “tortoise.” Both names are scientifically acceptable, though Testudines is more commonly used.

How are turtles classified scientifically?

Turtles are classified using the hierarchical Linnaean system from broad to specific: Domain (Eukaryota) → Kingdom (Animalia) → Phylum (Chordata) → Class (Reptilia) → Order (Testudines) → Family (14 options) → Genus (95+ options) → Species (350+ options). The specific family, genus, and species depend on the individual turtle’s evolutionary lineage and physical characteristics.

What family do snapping turtles belong to?

Snapping turtles belong to Family Chelydridae. This family contains 6 species divided into 2 genera: genus Chelydra (common snapping turtles with 3 species) and genus Macrochelys (alligator snapping turtles with 3 species).

All members share powerful jaws, aggressive defensive behavior, reduced plastrons, and ambush predation strategies.

Why do turtle scientific names use Latin?

Scientific names use Latin (or Latinized Greek) because it is a “dead language” that no longer changes, ensuring stability in naming. Latin was the language of educated Europeans when the modern classification system was developed in the 1700s by Carl Linnaeus.

Using Latin prevents confusion across different languages and countries. A Chinese scientist, Brazilian scientist, and American scientist all use Chelydra serpentina for the common snapping turtle, avoiding confusion from different common names.

How many turtle species are there?

There are approximately 350 living turtle and tortoise species currently recognized, though this number changes as new species are discovered and others are reclassified through genetic analysis.

The number has increased in recent decades as modern DNA sequencing reveals hidden diversity within populations once thought to be single species.

Related Articles

To deepen your understanding of turtles beyond taxonomy, explore these guides:

Types of Pet Turtles: Complete Species Guide

Sea Turtle Identification Guide: 7 Species Comparison

15 Fascinating Turtle Facts: Lifespan, Biology, and Behavior

Snapping Turtle Diet and Feeding Guide

About Author

Muntaseer Rahman started keeping pet turtles back in 2013. He also owns the largest Turtle & Tortoise Facebook community in Bangladesh. These days he is mostly active on Facebook.