Do Turtles Actually Breathe Through Their Butts?

This post was created with help from AI tools and carefully reviewed by a human (Muntaseer Rahman). For more on how we use AI on this site, check out our Editorial Policy.

I still remember the first time I heard this.

I was watching a nature documentary, half-asleep, when the narrator casually said, “Some turtles can breathe through their butts.”

I sat straight up.

Rewound it.

Watched again.

Then I Googled it.

And fell into the strangest rabbit hole of turtle biology I’d ever seen.

So here’s the truth: Yes, some turtles actually breathe through their butts.

But the full story is way more complicated than you’d think.

Let’s Clear Something Up First

Turtles have lungs.

They breathe air through their noses just like we do.

They can’t survive without oxygen.

So no, they don’t only breathe through their butts.

But under specific conditions, especially during winter, certain turtle species rely on something very special: cloacal respiration.

Sounds fancy, right?

Let’s break it down.

What Is Cloacal Respiration?

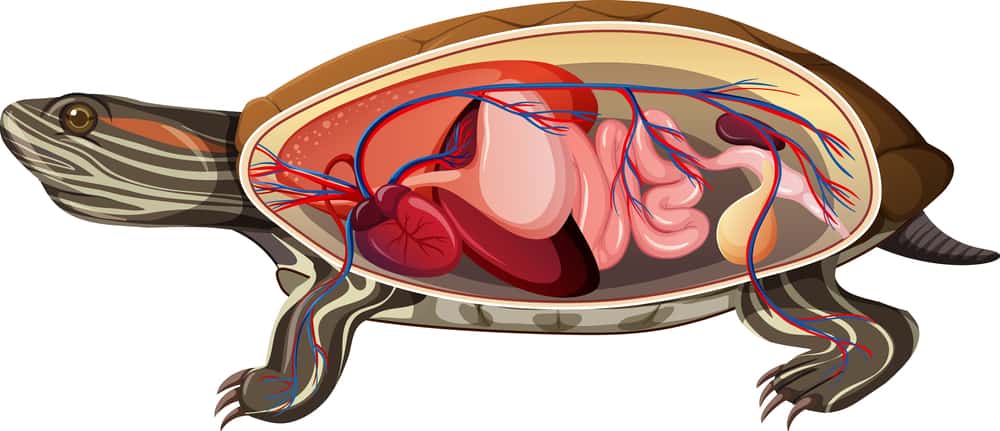

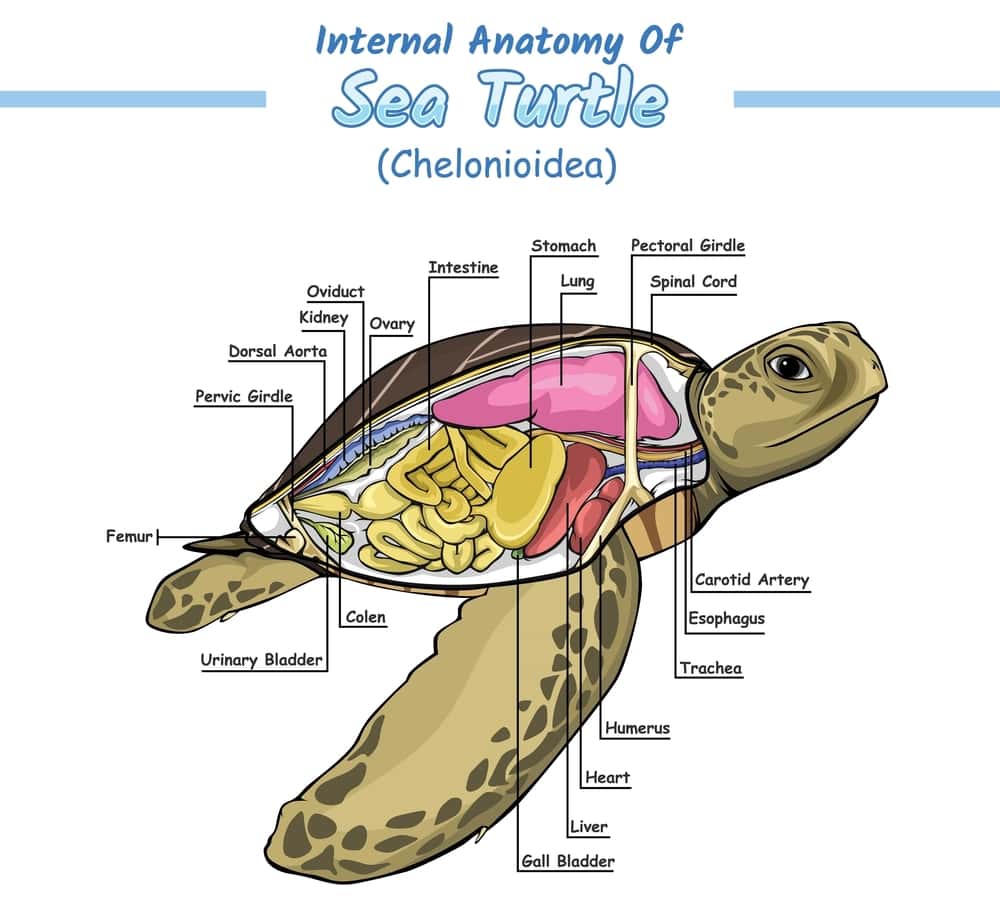

First, we need to talk about the cloaca.

It’s not technically a butt.

It’s a multipurpose opening that turtles use for pooping, peeing, laying eggs, and mating.

Think of it as nature’s Swiss Army knife.

In some turtle species, especially certain freshwater turtles, the cloaca has specialized sacs called bursae.

These sacs are lined with finger-like structures called papillae and packed with blood vessels.

When a turtle pumps water in and out of its cloaca, oxygen from the water diffuses across the papillae into the bloodstream.

It’s like having gills in your butt.

Only way cooler.

This Hilarious Turtle Book Might Know Your Pet Better Than You Do

Let’s be real—most turtle care guides feel like reading a textbook written by a sleep-deprived zookeeper.

This one’s not that.

Told from the snarky point of view of a grumpy, judgmental turtle, 21 Turtle Truths You’ll Never Read in a Care Guide is packed with sarcasm, sass, and surprisingly useful insights.

And hey—you don’t have to commit to the whole thing just yet.

Grab 2 free truths from the ebook and get a taste of what your turtle really thinks about your setup, your food choices, and that weird plastic palm tree.

It’s funny, it’s honest, and if you’ve ever owned a turtle who glares at you like you’re the problem—you’ll feel seen.

The Active Pumping Process

Here’s something most articles get wrong: turtles don’t just sit there passively soaking up oxygen.

They actively pump water in and out of their cloaca by contracting muscles.

It’s like rhythmic breathing, except through the wrong end.

The Fitzroy River turtle from Australia can take 15 to 60 cloacal “breaths” per minute.

That’s faster than some people breathe through their actual lungs.

Why Do Turtles Need This Weird Trick?

Picture this: you’re a turtle living in a pond in Canada.

Winter hits hard.

The pond freezes solid.

There’s a thick lid of ice preventing you from surfacing for air.

If you were a fish, you’d be fine since fish have gills.

But you’ve got lungs.

So what do you do?

This is where cloacal respiration becomes a lifesaver.

How Winter Changes Everything

When water temperature drops, so does a turtle’s body temperature.

They’re ectotherms (cold-blooded), which means their internal temperature matches their environment.

At near-freezing temperatures, their metabolism slows down dramatically.

Their heart rate drops to one or two beats per minute.

They barely move.

And instead of drowning, they slowly extract oxygen through their cloacal bursae.

Some species can survive like this for over 100 days without a single breath of air.

I once tried explaining this to my nephew.

He stared at me, horrified, and said, “So turtles drink air with their butts?”

Close enough, kid.

Which Turtles Can Actually Do This?

Here’s where things get interesting.

Not all turtles are butt breathers.

And the ones that are fall into two very different categories.

The Champions: Australian River Turtles

The absolute masters of cloacal respiration are Australian species:

- Fitzroy River turtle (Rheodytes leukops)

- White-throated snapping turtle (Elseya albagula)

- Mary River turtle (Elusor macrurus)

The Fitzroy River turtle is so good at this that scientists nicknamed it the “bum-breathing turtle.”

It can get up to 70% of its oxygen needs from water through its cloaca.

Under perfect conditions, it can stay underwater for 21 days straight.

Some researchers even believe it could potentially stay submerged indefinitely in oxygen-rich water.

These turtles live in fast-flowing rivers in Australia.

Going to the surface for air in strong currents is risky—you could get swept away.

So they evolved this adaptation to stay safe underwater.

The Misunderstood: North American Turtles

Now here’s where popular science gets it wrong.

You’ve probably heard that painted turtles and snapping turtles breathe through their butts during hibernation.

Turns out, that’s not quite accurate.

A 2025 study found that North American turtles overwintering under ice don’t actually use cloacal respiration in any significant way.

These turtles—including the famous painted turtle—belong to a different evolutionary branch called “hidden-necked turtles.”

The Australian butt-breathers are “side-necked turtles.”

These two groups split apart about 200 million years ago.

That’s older than the split between humans and platypuses.

So how do North American turtles survive winter under ice?

They absorb oxygen through their skin and the lining of their mouth (called buccal pumping).

Not their butts.

The cloacal bursae in these species are either non-functional for respiration or don’t contribute much.

Studies using painted turtles couldn’t demonstrate any significant oxygen uptake through the cloaca.

When Oxygen Runs Out

Even with their special breathing tricks, winter underwater is brutal.

Once ice seals a pond, there’s only so much dissolved oxygen in the water.

Aquatic plants that normally produce oxygen can’t photosynthesize under the ice.

Meanwhile, all the other pond creatures are using up what oxygen remains.

Eventually, the water becomes hypoxic (low oxygen) or even anoxic (zero oxygen).

When that happens, turtles switch to a last-resort survival mode: anaerobic respiration.

They create energy without oxygen.

But there’s a catch.

The Lactic Acid Problem

Anaerobic respiration produces lactic acid as a byproduct.

If you’ve ever done intense exercise and felt your muscles burn and cramp, that’s lactic acid buildup.

Turtles experience the same thing.

But painted turtles have one of the coolest adaptations I’ve ever heard of.

They use calcium from their own shells to neutralize the acid.

Their shells act like giant antacid tablets.

I literally laughed out loud when I first read this.

Nature is wild.

Spring Emergence: The Dangerous Time

When spring finally arrives, hibernating turtles are in rough shape.

They’re basically one big muscle cramp.

Their bodies are full of lactic acid.

They desperately need to bask in the sun to warm up, speed up their metabolism, and flush out the acidic byproducts.

But they’re slow and vulnerable.

This makes them easy targets for predators.

Spring can actually be more dangerous than winter for these turtles.

Butt Breathing vs. Regular Breathing

Even the expert butt-breathers can’t rely on cloacal respiration alone.

It’s supplemental, not a replacement.

Think of it like charging your phone with solar power—it works, but don’t expect lightning-fast results.

Cloacal respiration only provides enough oxygen when turtles are:

- Inactive

- In cold water (which slows metabolism)

- In oxygen-rich water

If a turtle is swimming around actively or stressed, it still needs to surface for air like normal.

Species That Lost The Ability

Here’s a fascinating detail: some turtles that you’d think would have cloacal bursae don’t.

Diamondback terrapins and sea turtles lost this ability through evolution.

Why?

They live in saltwater or brackish water.

You don’t want saltwater in direct contact with your bloodstream unless you’re a saltwater fish.

It’s the same reason sailors at sea can’t drink seawater.

Box turtles also lost their bursae because they’re terrestrial—they simply don’t need underwater breathing.

Scientists call these “secondary evolutionary losses.”

The turtles’ ancestors had this ability, but these species lost it because it wasn’t useful for their specific lifestyle.

Does This Make Turtles Special?

Absolutely.

This adaptation is one reason turtles have been around for over 200 million years.

They’ve outlived dinosaurs.

They’ve survived multiple mass extinctions.

It’s not glamorous.

It doesn’t involve flying or breathing fire.

But quietly extracting oxygen from water through your butt while trapped under ice for months?

That’s peak survival strategy.

Can Humans Do This?

Before you ask (and yes, people have asked), no—we can’t breathe through our butts.

There was some wild research during the pandemic when scientists tried rectal oxygen therapy on pigs and mice.

It worked to a small degree.

But humans don’t have cloacal bursae.

We just have regular butts with no special talents.

So please, don’t try anything weird.

Let the turtles have their moment.

The Bottom Line

The next time you see a turtle chilling underwater, remember this:

It might not be holding its breath.

If it’s an Australian river turtle, it could be actively pumping water through its cloaca, extracting oxygen like an underwater ninja.

If it’s a North American turtle hibernating under ice, it’s probably absorbing oxygen through its skin and mouth—not its butt, despite what you’ve heard.

Either way, turtles are doing things that would kill us in minutes.

And they’re doing it with the weirdest, most unexpected adaptations nature could cook up.

Through their butts (sort of).

That’s science at its strangest and most wonderful.

About Author

Muntaseer Rahman started keeping pet turtles back in 2013. He also owns the largest Turtle & Tortoise Facebook community in Bangladesh. These days he is mostly active on Facebook.