Turtle Anatomy 101: Do Turtles Have Teeth, Ears, Tails & More?

This post was created with help from AI tools and carefully reviewed by a human (Muntaseer Rahman). For more on how we use AI on this site, check out our Editorial Policy.

Ever looked at a turtle and wondered what’s actually going on under that shell?

I get it—these guys look like they’re basically just walking helmets with legs.

But trust me, turtle anatomy is way more interesting than it seems. Turtles don’t have teeth, and they definitely don’t hear like we do, but they’ve got some tricks that’ll make you rethink everything you thought you knew about reptiles.

Let’s break down the weird and wonderful body of turtles, from their toothless beaks to their hidden ears to their ability to literally breathe through their butts.

Do Turtles Have Teeth?

Short answer: Nope. Not even one.

Turtles, tortoises, and terrapins are completely toothless. Instead of teeth, they’ve got beaks—yeah, like birds.

These beaks are made of keratin (the same stuff as your fingernails), and they’re sharp enough to slice through food without any dental work required.

How Do Turtles Eat Without Teeth?

Think about it: if you had to eat a salad with scissors instead of teeth, you’d figure it out pretty quick. That’s basically what turtles do every day.

Different turtle species have different beak styles based on their diet:

Green Sea Turtles: These vegetarians have serrated ridges along the inside of their beaks that work like teeth. They use these edges to tear up seagrass and scrape algae off rocks in the ocean.

Loggerhead Turtles: These omnivores have massive, powerful jaws that can crush hard-shelled prey like crabs, clams, and sea urchins. They’re basically the nutcrackers of the turtle world.

Leatherback Turtles: These jellyfish specialists have soft, scissor-like jaws and something truly wild—spiny throat projections called papillae. These backward-facing spikes line their mouths and throats, keeping slippery jellyfish from swimming back out once they’re swallowed.

Snapping Turtles: Even though they’re famous for their aggressive bites, snapping turtles don’t have teeth either. They have strong, bony beaks shaped to bite off chunks of food. Their diet is mostly plant-based, but they’ll eat small mammals like ducks and mice when they get the chance.

It’s like each turtle species got a custom toolkit based on their favorite foods.

The Beak Advantage

So why did turtles ditch teeth in the first place?

Scientists believe having beaks allows turtles to cut their food more precisely and adapt more quickly to new food sources. Beaks are simpler to maintain—no cavities, no tooth decay, no dental visits required.

The keratin edge lining their jaws is very hard and sometimes serrated, making it look a little like a row of teeth. But these aren’t dental structures—they’re just really sharp edges.

The One Exception: Baby Turtles

Here’s where it gets interesting.

Baby turtles are actually born with an “egg tooth.” This small, sharp protrusion extends from the front of their beaks and is used to cut through their eggshell from the inside.

Think of it as nature’s can opener.

Turtle eggshells have leather-like strength and are difficult to crack open from the outside. But this temporary egg tooth—which is actually made of keratin, not real tooth material—helps hatchlings break free.

Once the hatchlings escape from the shell, this “tooth” falls off within the next several days. One-time use only, then it’s gone forever.

Did Ancient Turtles Have Teeth?

Wild fact: turtles weren’t always toothless.

A creature called “Odontochelys” (which literally translates to “toothed turtle”) existed about 200 million years ago—at the same time as dinosaurs. Fossil remains show this ancient ancestor had teeth on the roof of its mouth, in both the upper and lower jaws.

So turtles actually gave up teeth somewhere along the evolutionary road.

Evolution said “teeth are overrated” and turtles listened. Thanks to millions of years of evolution, modern turtles don’t need teeth at all.

Do Turtles Have Ears?

Yes—but you’ll never see them.

Turtles do not have external ears sticking out from their heads, and they don’t have eardrums like we do. Instead, they have thin flaps of skin covering internal ear structures.

It’s like having ears that are completely hidden behind skin.

The Hidden Ear Structure

If you look at a turtle’s head, the sides are smooth. No ear holes, no flaps, nothing.

But underneath that skin, turtles have a complete internal ear system. They have middle ears and inner ears with all the auditory nerves and mechanisms needed for hearing.

The thin skin flap (called a cutaneous plate) that covers the ear receives vibrations and low-frequency sound waves from the sides of their head. For some species like red-eared sliders, you can actually spot this area—it’s the red stripe on the side of their head.

How Turtle Hearing Actually Works

Picture this: instead of sound funneling into your ear like a satellite dish, turtles pick up vibrations through these skin flaps.

Sound waves hit the cutaneous plate, which vibrates and sends low-frequency sound waves into the ear canal. The internal ear receives both the vibrations and low-frequency sounds and amplifies them. The inner ear contains hair cells and auditory nerves that convert the sound waves to electrical impulses, which are then transmitted to the brain for interpretation.

But here’s the catch: turtles have a much narrower hearing range than humans.

Turtle hearing range: 50–1,000 Hz (best around 200–750 Hz)

Human hearing range: 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz

So they can’t hear everything we hear. Turtles are incapable of hearing high-frequency sounds such as the chirping of birds (which have frequencies between 1,000 Hz and 8,000 Hz). But they can sense vibrations and low-frequency sounds like drums, wings flapping, or footsteps.

Understanding how turtles hear is crucial when assessing their defense mechanisms against predators, since they rely on detecting low-frequency vibrations like footsteps and wing flaps to sense approaching threats.

What CAN Turtles Hear?

Turtles are sensitive to:

- Low-frequency sounds and vibrations

- Changes in water pressure (which might indicate a predator nearby)

- Crashing waves and ocean sounds

- Vessel motors and low rumbling sounds

- Vibrations on their shell (they can “hear” when their shell is touched)

What they CAN’T hear:

- High-pitched bird songs

- Human voices in higher registers

- Most sounds above 1,000 Hz

Turtles Hear Better Underwater

Here’s the kicker: turtles and tortoises can hear better underwater than on land.

Why? These species have large, air-filled sacs inside their skulls that vibrate more strongly underwater since sound waves travel faster in water. There’s also a subcutaneous layer of fat inside their ears that acts as a conductor for sound underwater.

Basically, water turns up the volume for them.

Sea turtles are most sensitive to low-frequency sounds below 1,000 Hz, such as the sounds of crashing waves or vessel motors. They’re tuned in to the ocean’s rhythm. This makes sense when you think about it—many turtle species spend most of their time in water, so having ears adapted for underwater hearing is way more useful than hearing in air.

Are Turtles Deaf?

Absolutely not.

For a long time, people thought turtles were deaf because they don’t have visible ears and early studies failed to detect their hearing. But we know now that turtles can hear—they just hear differently than we do.

Hearing is actually a secondary sense for turtles. Their primary senses are vision and smell, which they rely on much more heavily for survival.

This Hilarious Turtle Book Might Know Your Pet Better Than You Do

Let’s be real—most turtle care guides feel like reading a textbook written by a sleep-deprived zookeeper.

This one’s not that.

Told from the snarky point of view of a grumpy, judgmental turtle, 21 Turtle Truths You’ll Never Read in a Care Guide is packed with sarcasm, sass, and surprisingly useful insights.

And hey—you don’t have to commit to the whole thing just yet.

Grab 2 free truths from the ebook and get a taste of what your turtle really thinks about your setup, your food choices, and that weird plastic palm tree.

It’s funny, it’s honest, and if you’ve ever owned a turtle who glares at you like you’re the problem—you’ll feel seen.

Do Turtles Have Tails?

Every single one.

Yes, turtles have tails, and they come in different shapes and sizes depending on the species and gender.

Male and female turtles have different-sized tails—males have longer and wider tails than females. In fact, once sea turtles reach sexual maturity, the size of the tail is one of the most reliable ways to tell males from females. Males develop much longer tails that may extend past their rear flippers, whereas female tails remain much shorter.

What’s the Tail For?

Tails in turtles serve several important functions.

Unlike snakes and fish, turtles have legs, so they don’t need tails for locomotion or swimming. But that doesn’t mean tails are useless—far from it.

Protection of the Cloaca

The primary purpose of the tail is to protect the cloaca and the vent.

The cloaca is a posterior opening that serves multiple functions—it’s used for digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts. In both male and female turtles, the cloaca stores excretory waste that’s released outside through the vent. The tail covers this vulnerable opening, acting as a protective barrier.

The tail’s role in protecting the cloaca is particularly important for turtles with defensive strategies that don’t include full shell retraction, such as snapping turtles that must rely on their aggressive nature instead.

Reproduction

Here’s where it gets wild: the male sexual apparatus is located in the tail.

The penis is situated at the base of the male turtle’s tail. During mating, male turtles use their tails to find the cloacal opening on female turtles. Without the tail, locating this opening would be nearly impossible because of the turtle’s shell and body structure.

The tail also helps males maintain their balance while mating. The sensitive tip of the tail can scan the area to locate the female’s cloaca and guide the male into the right position.

Female turtles also use their tails during reproduction. When mating or laying eggs, females move their tails upward or to the sides to expose the cloaca, making it accessible to males or providing an opening for egg-laying.

The male’s tail also serves a passive function during mating—it covers the female’s cloacal entrance while mating, making it impossible for other males to mate with the same female at the same time. Nature’s “occupied” sign.

Balance and Stability

When turtles need to find equilibrium on rocky ground or navigate difficult terrain, their tails help them stabilize their footing.

Box turtles and snapping turtles, in particular, use their tails for balance. Snapping turtles actually have the longest tails of all turtle species—their robust tails help stabilize their body movement during uphill climbs.

Breathing During Hibernation

Wild fact: turtles use their cloacal opening to breathe during hibernation.

During brumation (reptile hibernation), they move their tails slightly to allow water to enter the cloaca for oxygen absorption. More on this insane ability later.

Can Turtles Regrow Their Tails?

Nope. Not like lizards.

Though turtles are reptiles, their entire tails do not regrow like a lizard’s tail can. When turtles lose their tails due to injury or predators, the wounds can heal over time with proper care, but the tail won’t grow back completely.

Minor wounds on the tail will eventually recover. But if a turtle suffers a serious tail injury that damages the cloaca, it can be fatal because of the accumulation of excrement and the loss of reproductive function in males.

This is why you should never pick up a turtle by its tail—it’s a sensitive and vital part of their anatomy.

Tail Differences Between Species

Sea Turtles: Adult males have very long tails that extend well past their rear flippers. Females have short, stubby tails.

Box Turtles: Short tails that are mostly hidden under the shell.

Snapping Turtles: The longest tails of any turtle species—sometimes as long as their entire shell.

Big-Headed Turtles: Also have notably long tails compared to other freshwater species.

The shape and length of the tail depends on the species, gender, and the turtle’s specific lifestyle needs.

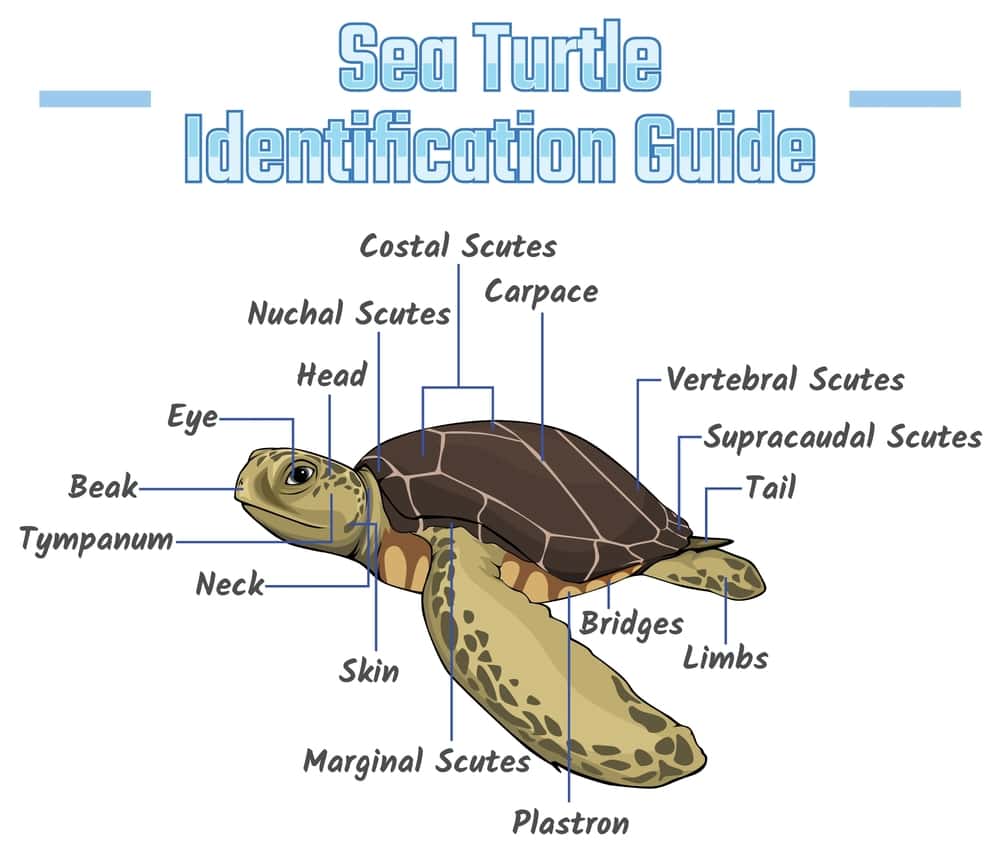

The Shell: Not Just a Pretty Cover

Let’s talk about the most obvious turtle feature—the thing that makes a turtle a turtle.

The shell isn’t just some hollow dome that turtles crawl into. It’s a complex structure made of bone and keratin that’s literally fused to the turtle’s skeleton.

Shell Basics

Turtle shells are made of over 50 bones fused together—so they’re literally wearing their bones on the outside. The shell has two main parts:

Carapace: The top (dorsal) part of the shell. Usually domed and formed from fused ribs and vertebrae.

Plastron: The bottom (ventral) part of the shell, covering the turtle’s belly.

The two halves meet along the sides at a bony bridge, creating a rigid “shell box” around the body. Because the ribs and spine are fused to the shell, a turtle cannot crawl out of it—the shell grows with the turtle and is permanently attached.

The Bones Inside

The shell contains around 50 to 60 bones, including roughly 10 fused trunk vertebrae and rib bones that have expanded and joined together.

Here’s what makes turtle anatomy truly weird: a turtle’s shoulder blades and pelvis are located inside the ribcage. Most animals have shoulder blades outside their ribs, but turtles evolved to have their entire skeletal structure encased within the shell.

The carapace is made up of several types of bones:

- Proneural plate: Single bone at the center front of the shell nearest to the head

- Neural plates: About 8 plates that run down the midsection of the shell toward the tail

- Suprapygal plates: Two bones located after the neural plates at the end of the shell

- Pygal plate: At the tail end of the shell

- Peripheral plates: About 22 plates located along the edge of the carapace

- Pleural/Costal plates: These are the expanded rib bones

The plastron consists of about nine bones including:

- Epiplastra: Two bones at the front (homologous to collarbones)

- Entoplastron: One medial bone (homologous to the interclavicle)

- Hyoplastra: Four bones in the middle section

- Xiphiplastra: Two bones at the rear

The Scutes: Turtle Armor

On top of all those bones is another layer of protection—scutes.

Scutes are scales made of keratin (same stuff as your fingernails and hair) that cover the outer surface of the shell. They overlap like shingles and protect the bony shell underneath from scrapes, bruises, and injury.

Typically, a turtle has 38 scutes on the carapace and 16 on the plastron, giving them 54 in total.

The scutes on the carapace are divided into:

- Nuchal scute: Directly behind the turtle’s head (sometimes absent)

- Vertebral scutes: Five central scutes down the middle of the carapace

- Costal scutes: Four pairs of scutes on either side

- Marginal scutes: About 24 small scutes around the edge

The plastron scutes include:

- Gulars (throat)

- Humerals

- Pectorals

- Abdominals

- Anals

Side-necked turtles also have “intergular” scutes between the gulars.

Shell Growth and Shedding

Because a turtle’s shell is an integral part of its anatomy, it must expand as the turtle grows.

New scutes are produced in the thin layer of tissue covering the bony skeleton (called the epithelium), growing up from under the existing scutes. Land turtles (tortoises) add growth rings to their scutes each year, which can give a rough estimate of age—kind of like tree rings.

Aquatic turtles shed their scutes periodically. This shedding helps reduce the shell’s thickness so it stays streamlined and helps remove algae or infections on the surface.

When you see an aquatic turtle shedding, it looks like the shell is peeling off in layers. This is totally normal.

Can Turtles Leave Their Shells?

Absolutely not.

The shell IS the turtle. The carapace is fused with the vertebrae and ribs, while the plastron is formed from bones of the shoulder girdle, sternum, and gastralia (abdominal ribs).

You can’t separate a turtle from its shell any more than you can remove your own ribcage. It’s attached permanently. A turtle without its shell is a dead turtle—the shell holds the turtle together and houses its organs.

Shell Variations

Not all turtle shells are the same. Evolution has created some interesting variations:

Box Turtles: Some species have hinges on their shells (usually on the plastron) that allow them to completely close up inside their shell. The front and back sections can close like a box, protecting them completely from predators.

Softshell Turtles: These species have lost most of the bony layer and dumped the hard scutes in favor of tough, leathery skin. This makes them much lighter and faster swimmers. Their plastron is modified into strut-like supports instead of a solid casing.

Leatherback Sea Turtles: The only turtle species to have basically dumped its shell completely. Instead of bony plates, they have many small interwoven bones covered by thick, cartilaginous, leathery skin. This flexible shell allows them to dive to depths over 1,000 meters without being crushed by water pressure.

Keeled Shells: Some species like map turtles and several sea turtles have a raised ridge (keel) running down the center of the carapace from front to back.

Shell Size Extremes

Turtle shells come in wildly different sizes:

Smallest: The Chersobius signatus (speckled padloper tortoise) from South Africa measures no more than 10 cm (3.9 inches) in length and weighs just 172 grams (6.1 ounces).

Largest living: The leatherback turtle can reach over 2.7 meters (8 feet 10 inches) in length and weigh over 500 kg (1,100 pounds). The world record was a leatherback found in Wales in 1988 measuring 2.5 meters long and weighing over 900 kg.

Largest ever: Archelon ischyros, a Late Cretaceous sea turtle, reached up to 4.5 meters (15 feet) long and 5.25 meters (17 feet) wide between the tips of the front flippers. It’s estimated to have weighed over 2,200 kg (4,900 pounds).

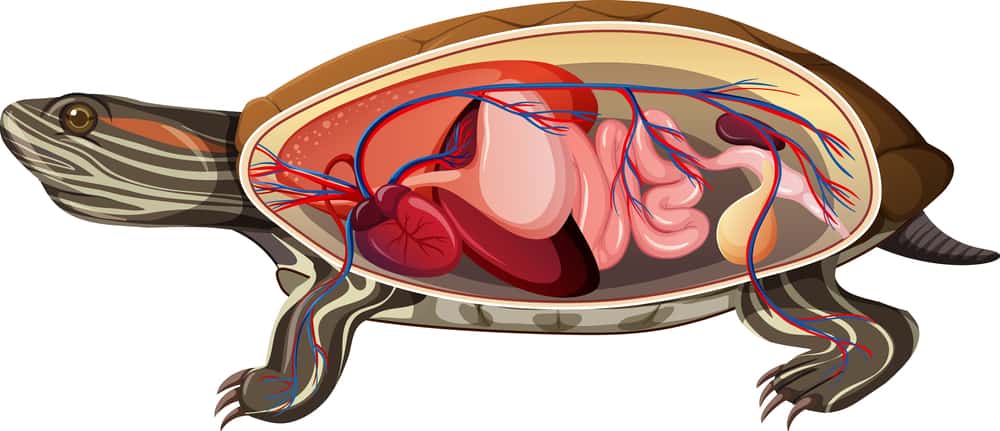

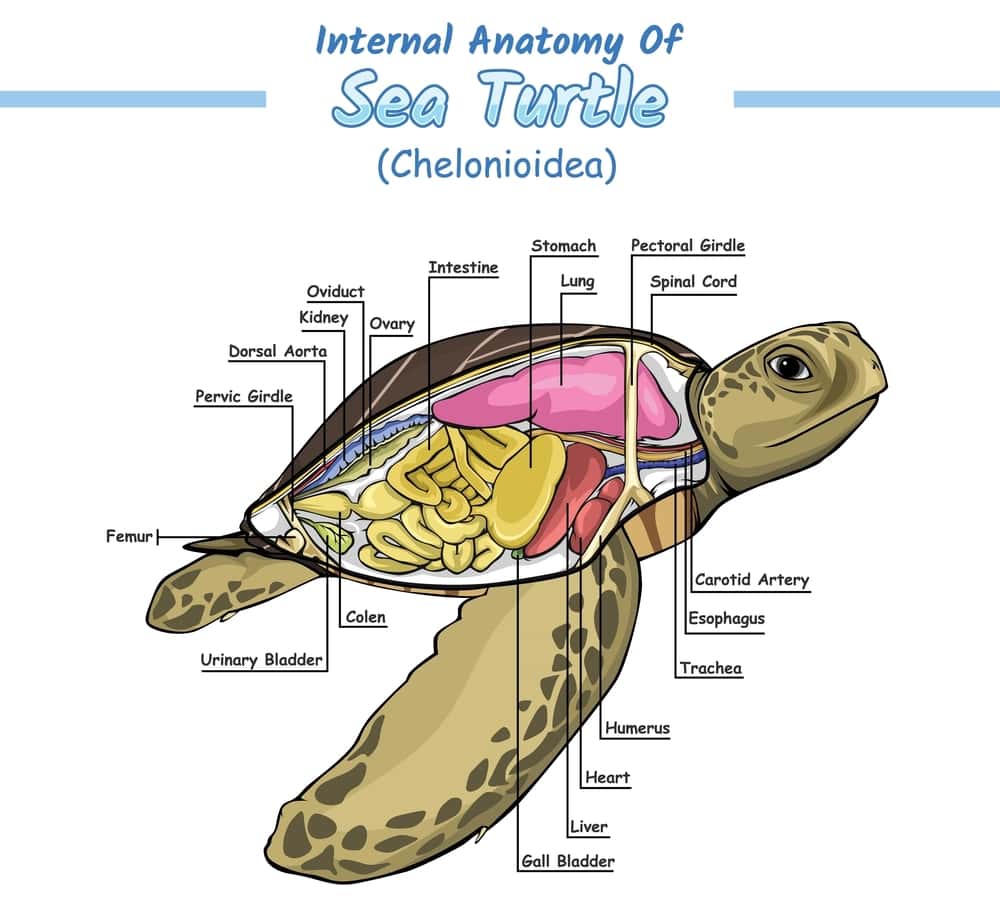

Internal Organs: What’s Inside the Shell?

The shell isn’t hollow—it’s packed with organs.

Because turtles have their ribs and spine fused to the shell, their internal organs are arranged differently than other animals.

Lungs

Turtles have two lungs located near the top of the shell, right under the carapace.

But here’s the problem: turtles can’t expand their ribcage to breathe like we do because their ribs are fused to the shell. So how do they get air in and out?

Turtles use specialized abdominal muscles that line the inside of their shells. These muscles run from the pelvic girdle to the shoulder girdle to the plastron, and they contract and relax to move air in and out of the lungs.

Turtles can also alter the pressure in their lungs by moving their limbs in and out of the shell. When they pull their limbs in, it increases pressure and helps expel air. When they extend their limbs, it creates more space for air to enter.

Air enters through the nostrils (which are always open and lack valves), moves through the glottis (which opens and shuts), flows into the trachea, and then into the lungs through the bronchi. Gas exchange happens at the bronchioles.

Heart and Circulatory System

Turtles have a three-chambered heart (two atria and one ventricle) located in the middle of the body, underneath the lungs.

As cold-blooded animals (ectotherms), their internal temperature varies with their environment. If the water is 60°F, their body temperature is 60°F. This affects their metabolism and oxygen needs.

Digestive System

The digestive tract winds through the turtle’s body from the mouth to the cloaca.

Turtles are generally opportunistic omnivores—they eat both plants and animals with limited movement. Because they don’t have teeth to chew, they bite off chunks with their beaks and swallow food in larger pieces.

The stomach breaks down food, and nutrients are absorbed through the intestines. Waste is stored in the cloaca before being expelled.

The Cloaca: The All-Purpose Opening

The cloaca is one of the most important structures in turtle anatomy.

This single opening serves as the exit point for:

- Digestive waste (feces)

- Urinary waste (urine)

- Reproductive functions (mating and egg-laying)

- Breathing (during hibernation via cloacal respiration)

Basically, it’s an all-in-one system. And yes, this means turtles pee, poop, and mate from the same opening. Nature is efficient, if not elegant.

The Weirdest Thing: Butt Breathing

Yeah, you read that right. Turtles can breathe through their butts.

When turtles hibernate underwater during winter, their main source of oxygen comes through their cloaca. Technically, the term is “cloacal respiration,” and it’s not quite breathing like we do—it’s more like diffusing oxygen in and carbon dioxide out.

But the fact remains: turtles can get oxygen through their butt.

How Does Butt Breathing Work?

Through cloacal respiration, turtles get oxygen from the water by moving it over body surfaces covered in blood vessels.

Here’s the process:

- Water pumping: Turtles contract their cloacal muscles to draw water into two specialized sacs within the cloaca called bursae (singular: bursa).

- Gas exchange: The bursae are lined with tiny finger-like projections called papillae that contain a dense network of blood vessels. As water flows over these papillae and blood vessels, oxygen in the water diffuses across them into the turtle’s bloodstream.

- Water expulsion: The turtle expels the oxygen-depleted water and pumps fresh water back into the bursae to start the process again.

It’s basically like having gills in your butt. The bursae function exactly like fish gills—just located in a very different place.

When Do Turtles Use Cloacal Respiration?

Cloacal respiration is especially useful during colder months when ponds and rivers freeze over.

When the temperature drops in winter, a turtle’s internal temperature drops with it, and its metabolism slows way down to match. While they’re in this slowed-metabolism hibernation period (called brumation), their oxygen needs are quite low. The oxygen absorbed through cloacal respiration is enough to sustain them until spring.

During brumation, turtles rely on stored energy and oxygen uptake from the pond water. They can stay underwater for well over 100 days using cloacal respiration and anaerobic metabolism.

Some turtles are better at this than others:

Champions: The Fitzroy River turtle from Australia can derive 100% of its energy through cloacal respiration. This allows them to potentially remain underwater indefinitely.

Good at it: Painted turtles, snapping turtles, white-throated snapping turtles, and Mary River turtles can all use cloacal respiration effectively.

Not capable: Sea turtles, diamondback terrapins, box turtles, and tortoises don’t have cloacal bursae and can’t do this.

During these extended underwater periods, turtles also face the risk of ending up upside down and being unable to surface for air, which makes their ability to breathe through their cloaca even more critical for survival.

Why Don’t All Turtles Have This Ability?

Not all turtles have cloacal bursae. Here’s why:

Sea turtles: Don’t have them because they live in saltwater. Unless you’re a saltwater fish, you don’t want saltwater coming in direct contact with your bloodstream—it’s like drinking seawater, which will kill you.

Diamondback terrapins: Live in brackish water (mix of salt and fresh), so they’ve lost their bursae as an evolutionary adaptation.

Box turtles: Are terrestrial and have no use for underwater breathing, so they’ve lost the bursae.

Snapping turtles: Oddly, even though they’re aquatic, they don’t have cloacal bursae. They tend to walk on the bottom more than swim, so maybe that’s why.

Softshell turtles also don’t have them, and scientists aren’t sure why since they’re highly aquatic swimmers.

The Downsides of Butt Breathing

Cloacal respiration is much less efficient than normal aerobic respiration.

Pumping water into the bursae requires a lot of energy, which reduces the net energy gain. When we breathe air, there’s virtually no energy required because gases are light and flow freely. But imagine trying to breathe a viscous liquid back and forth—that’s what turtles do.

Water also has about 200 times less oxygen than an equal volume of air, so turtles have to pump way more of it to gain the same amount of oxygen.

There’s also another cost: when oxygen diffuses into the bloodstream, sodium and chloride ions (charged particles) that are vital to cell functioning diffuse in the opposite direction into the water. This can mess with cellular function.

Plus, in a closed space like an iced-over pond, oxygen in the water can run out. If times get really tough, turtles can switch to anaerobic respiration—powering their metabolism without oxygen—but this comes with a time limit due to the buildup of lactic acid.

Butt Breathing in Other Animals

Turtles aren’t alone in this bizarre ability.

Cloacal respiration is fairly common among amphibians and reptiles. Notable users include frogs, salamanders, and sea snakes. Sea cucumbers also use cloacal respiration via a pair of “respiratory trees.”

Research has even shown that mammals—including mice and pigs—are capable of a form of intestinal respiration in laboratory settings, though it’s far less efficient than in turtles.

Turtle Vision: What Can They See?

Turtles have excellent vision, especially underwater.

Color Vision

Turtles make use of vision to find food and mates, avoid predators, and orient themselves. They have full-color vision in bright light.

The retina’s light-sensitive cells include both rods (for vision in low light) and cones with three different photopigments for bright light. There may even be a fourth type of cone that detects ultraviolet light—hatchling sea turtles respond to UV light experimentally.

One freshwater turtle, the red-eared slider, has an exceptional seven types of cone cells. That’s more color receptors than humans have (we only have three).

Sea turtles can see:

- Near-ultraviolet

- Violet

- Blue-green

- Yellow light

They are NOT sensitive to light in the orange to red range of the visible spectrum.

Vision in Water vs. Land

Sea turtles can see well underwater but are nearsighted out of water.

The cornea (the curved surface that lets light into the eye) doesn’t help focus light on the retina in turtles like it does in humans. For aquatic turtles, focusing underwater is handled entirely by the lens.

Sea turtles can use their eyes effectively in:

- Clear surface water

- Muddy coasts

- The darkness of the deep ocean

- Above water (though not as clearly)

They orient themselves on land by night using visual features detected in dim light.

No Peripheral Vision

Although tortoises and many turtles have well-developed vision, they do not have peripheral vision. They need to turn their heads to see things to the side.

Turtle Sense of Smell

Turtles have an excellent sense of smell, both on land and underwater.

They have specialized structures for smelling—instead of just nostrils, they have bumps with nerves that allow them to detect scents. Sea turtles can smell in water, and experiments show that hatchlings react to the scent of shrimp.

This adaptation helps sea turtles locate food in murky water where vision might be limited.

The sense of smell plays an important role during mating season. Male turtles find female turtles by picking up the female’s pheromones.

Turtle Sense of Touch

Turtles are surprisingly sensitive to touch.

You might think that turtles wouldn’t be sensitive because of their thick skin and shells, but they actually have various nerves running along their skin and shell that enable them to feel when they’re touched.

This sensitivity, combined with the inner ear structures, allows them to “hear” where their shell has been touched through vibrations.

This is why it’s discouraged to unnecessarily handle pet turtles—being touched can be stressful for them even though they can’t always escape or show visible signs of distress.

Turtle Limbs and Movement

Turtle limbs vary dramatically based on whether they live on land, in freshwater, or in the ocean.

Sea Turtles

Sea turtles and the pig-nosed turtle are the most specialized for swimming.

Their front limbs have evolved into flippers while the shorter hind limbs are shaped more like rudders. The front flippers provide most of the thrust for swimming, while the hind limbs serve as stabilizers.

Sea turtles like the green sea turtle rotate their front flippers like a bird’s wings to generate propulsive force on both the upstroke and downstroke. Combined with their streamlined shells that reduce drag, marine turtles swim about six times faster than freshwater turtles.

Freshwater Turtles

Freshwater turtles have webbed feet with claws.

They use their front limbs more like the oars of a rowing boat, which creates substantial negative thrust on the recovery stroke. They’re decent swimmers but not nearly as efficient as sea turtles.

Land Turtles (Tortoises)

Land-dwelling turtles have sturdy, elephantine legs with strong claws for digging.

Their feet are adapted for walking on land rather than swimming. Box turtles and tortoises have short, stumpy legs that support their heavy, dome-shaped shells.

Special Adaptations

Turtles have evolved some truly wild adaptations over their 200+ million-year existence.

Temperature Regulation

As ectotherms (cold-blooded animals), turtles rely on external sources of heat to regulate their body temperature.

If the pond water is 1°C, the turtle’s body is 1°C. If it’s 30°C, the turtle is 30°C. This is why you see turtles basking in the sun—they’re literally charging their batteries.

When a turtle’s body temperature changes, it’s simply because the environment has become warmer or colder. For humans, a change in body temperature is a sign of illness. For turtles, it’s Tuesday.

Salt Glands

Sea turtles have specialized salt glands near their eyes that excrete excess salt from swallowing seawater.

This is why sea turtles sometimes look like they’re crying—they’re actually getting rid of excess salt through a gland near the corner of their eye. The salt concentration excreted can be twice that of seawater.

Magnetic Navigation

Sea turtles have an internal compass that allows them to navigate using Earth’s magnetic field.

Hatchlings use this to orient themselves after swimming through the surf zone. Adults use it to stay on course while migrating—some sea turtles migrate thousands of miles back to the same nesting beaches where they were born.

The leatherback sea turtle holds the record for the longest known migration: a female swam nearly 13,000 miles over 647 days from Indonesia to the west coast of America. That’s over 20 miles per day for nearly two years.

Longevity

Turtles are famous for living a really long time.

The survival rate for adult turtles can reach 99% per year. Water turtles generally live 30–40 years, but box turtles and tortoises can live between 50–100 years.

The oldest living turtle is said to be Jonathan, a Seychelles giant tortoise who turned 187 in 2019. A Galápagos tortoise named Harriet, collected by Charles Darwin in 1835, died in 2006 after living for at least 176 years.

Turtles keep growing new scutes every year, and they age slowly. Most wild turtles don’t reach these extreme ages due to predators, disease, and environmental threats, but their potential lifespan is remarkable.

Hibernation/Brumation

Many freshwater turtles that live in northern climates spend the entire winter submerged underwater in a state called brumation (reptile hibernation).

During brumation:

- Their metabolism slows to almost nothing

- Their body temperature matches the water temperature

- They don’t eat for months

- They rely on stored energy and cloacal respiration for oxygen

- They can survive for over 100 days without surfacing

Both snapping turtles and painted turtles can survive forced submergence at cold water temperatures in the lab for well over 100 days.

Why Turtle Anatomy Matters

Look, turtles have been around for over 200 million years.

They’ve survived dinosaurs, ice ages, and basically everything else the planet could throw at them. Their anatomy is the result of millions of years of evolution that said “forget teeth, forget visible ears, and definitely keep that shell.”

These animals are walking proof that you don’t need conventional body parts to be wildly successful. They’ve adapted to life on land, in freshwater, and in oceans—all with the same basic body plan that looks like it was designed by a committee that couldn’t agree on anything.

And honestly? That’s what makes them so cool.

Conservation Concerns

Unfortunately, understanding turtle anatomy isn’t just academically interesting—it’s crucial for conservation.

All six species of sea turtles in the United States are listed and protected under the Endangered Species Act. It’s estimated that only 1 in 1,000 marine turtle hatchlings make it to adulthood due to the long time it takes them to reach maturity and the many dangers they face.

Major threats include:

- Getting accidentally caught in fishing gear

- Plastic pollution (over 50% of marine turtles have ingested plastic)

- Habitat destruction and loss of nesting beaches

- Climate change (affecting sand temperature and sex ratios of hatchlings)

- Hunting and illegal trade

Understanding how turtles hear, for example, helps us assess how they might be impacted by human-generated ocean noise and develop methods to reduce these impacts.

Knowing how their shells grow and develop helps us treat injured turtles and understand what they need to thrive.

Learning about their reproductive anatomy helps us protect nesting sites and support breeding programs.

The Bottom Line

Next time you see a turtle, remember: that’s not just a slow reptile in a shell.

That’s a breathing, hearing, tail-having, beak-wielding survival machine with:

- A skeleton fused into a portable fortress

- Internal ears that work better underwater than on land

- A tail that serves as both protection and a reproductive tool

- A beak instead of teeth that’s perfectly adapted to its diet

- The ability to literally breathe through its butt when winter comes

- Over 50 bones making up its shell

- Internal organs arranged in a completely unique way

- Senses adapted for both land and water

- An evolutionary history spanning hundreds of millions of years

If that’s not impressive, I don’t know what is.

Turtles took the basic reptile body plan and went completely off-script. No teeth? No problem—use a beak. Can’t expand your ribcage to breathe? No worries—use specialized muscles and, when needed, your butt. Need to protect your entire body? Fuse your ribs into an indestructible fortress.

They’re weird, they’re wonderful, and they’ve been perfecting their bizarre anatomy for longer than most other animals have existed on this planet.

So yeah, turtles might move slow, but they’re way more impressive than they look. And now you know why.

About Author

Muntaseer Rahman started keeping pet turtles back in 2013. He also owns the largest Turtle & Tortoise Facebook community in Bangladesh. These days he is mostly active on Facebook.